Daily life for the European Colonists in New England

Sources:

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/

https://www.genealogymagazine.com/colonial-love-marriage/

http://mayflowerhistory.com/clothing

https://www.themayflowersociety.org/blog/dress-like-a-pilgrim

https://www.plimoth.org/learn/just-kids/homework-help/what-wear#Pilgrim%20clothing

Marriage

Marriage was a working partnership. A spouse was needed to help with managing the work necessary to support and care for a family. There were far more men than women in colonial New England, which meant that most women had no trouble finding a husband. Most men married in their mid to late 20s when they were prepared to support a family. Women might marry as early as 15 or 16.

It was the Puritan belief that since the Bible said little about marriage, it should be a civil matter rather than a religious one, so marriages were performed by magistrates rather than the clergy. Since marriages were not considered sacramental and indissoluble, the Puritans granted divorces for desertion, bigamy, adultery, and failure to provide. Women received divorces more often than men. However, there were far more petitions for divorce than were granted.

When a colonial woman married, she gave up most legal rights as an individual and her property went under her husband’s management. She was legally bound to obey her husband, just as she would obey God. However, the colonies limited or outlawed physical abuse of wives. In 1641, for instance, Massachusetts prohibited wife beating “unless it be in his own defense upon her assault.”

Because the death rate was so high, newlyweds had only a one-in-three chance of living together for over 10 years. Many men and women married two or more times, often within months of the death of the previous spouse.

Childbirth

A belief that hard work made for easier labor meant that women spun thread, wove clothing, and performed heavy lifting while pregnant. Women assumed significant risks when they gave birth. A general lack of doctors in Colonial New England, along with the popular belief that it was indecent for a man to be present during childbirth meant that midwives performed the majority of in-home births, with no painkillers to assist the mother except alcohol. A

woman's chances of dying during childbirth were between 1.5 and 2 percent - for each birth. The average women gave birth to six to ten children, so her chances of eventually dying in childbirth were high. The infant mortality rate was lower than

it had been in England, probably due to the less crowded conditions, but records were scarce, so accurate information is hard to come by. Infant mortality rates are estimated to be anywhere from 20%-30% in the first five

years.

A belief that hard work made for easier labor meant that women spun thread, wove clothing, and performed heavy lifting while pregnant. Women assumed significant risks when they gave birth. A general lack of doctors in Colonial New England, along with the popular belief that it was indecent for a man to be present during childbirth meant that midwives performed the majority of in-home births, with no painkillers to assist the mother except alcohol. A

woman's chances of dying during childbirth were between 1.5 and 2 percent - for each birth. The average women gave birth to six to ten children, so her chances of eventually dying in childbirth were high. The infant mortality rate was lower than

it had been in England, probably due to the less crowded conditions, but records were scarce, so accurate information is hard to come by. Infant mortality rates are estimated to be anywhere from 20%-30% in the first five

years.

Childhood

Children growing up in colonial America, didn't have the luxury of a carefree childhood. Even for children from wealthier families, there were expectations of how a child should contribute to the needs of the family. For the working class and rural farmers, the more children you had, the more contributors there were to help you survive and prosper. Mothers taught their girls to spin, knit, cook, and produce household items, while fathers taught their sons how to wield a gun, a compass, and an ax. Parents could be very demanding and harsh with their children, but since all children experienced much the same thing, there was little context for feeling mistreated. In the country, children would help with the crops or livestock or with preserving food, spinning thread and weaving cloth. In the towns, children might work under the supervision of their mother or father, learning their occupation.

Children growing up in colonial America, didn't have the luxury of a carefree childhood. Even for children from wealthier families, there were expectations of how a child should contribute to the needs of the family. For the working class and rural farmers, the more children you had, the more contributors there were to help you survive and prosper. Mothers taught their girls to spin, knit, cook, and produce household items, while fathers taught their sons how to wield a gun, a compass, and an ax. Parents could be very demanding and harsh with their children, but since all children experienced much the same thing, there was little context for feeling mistreated. In the country, children would help with the crops or livestock or with preserving food, spinning thread and weaving cloth. In the towns, children might work under the supervision of their mother or father, learning their occupation.

There were some large families of 12-16 children, but the average husband and wife had 6-10 children. Since 50% of children died before they reached adulthood, the functional size of families was usually much smaller. Diseases, while affecting all ages, were common causes of death in childhood. Whooping cough, diphtheria, dysentery, tuberculosis, typhus, typhoid fever, rickets, chicken pox, measles, scarlet fever, smallpox and plague, under their period names, were all listed as causes of death in children. Some deaths were caused by accidents, the most common being drowning. Small children fell into laundry tubs, or played too close to ditches, ponds and wells. Older children died while playing near water, swimming or bathing, or while working. Both boys and girls living near the shore gathered shellfish and were swept in by waves. Boys drowned while fishing or gathering reeds. Older girls slipped into pits, ditches or ponds while drawing water. Burning was a less common cause of death, although babies left in cradles near the fire and unsupervised toddlers were at risk. Children were also occasionally killed by a cart or horse.

Adults also had high mortality rates, which meant that children were likely to lose at least one parent before they married. The majority of colonial children spent at least some time under the supervision of a stepparent. Children legally belonged to their fathers. When a father died, the court assigned guardianship of the children to another male, even if the mother was still living. Legal guardianship applied to protecting the child’s property and legal rights, rather than day-to-day care of the children. Children were given some say in choosing their guardians.

Education

https://noahwebsterhouse.org/colonial-schools

In the 1600s, many adults were illiterate. Most of the colonial population were at least part-time farmers, which meant that for some, an in-depth education was unnecessary. However, Puritans emphasized literacy so everyone could read the Bible. Children received a rudimentary education in their families and parents taught them the

basics of religion. Early New England communities supported free public schools. Students from four to twenty years old studied in one-room schoolhouses where there was usually one schoolmaster for all grades. They learned reading, writing, and simple math. Boys usually went to school in the winter when there were fewer farm chores for them to do, while girls and younger children went to school in the summer. When their parents needed them to work at home, they did not go to school.

In the 1600s, many adults were illiterate. Most of the colonial population were at least part-time farmers, which meant that for some, an in-depth education was unnecessary. However, Puritans emphasized literacy so everyone could read the Bible. Children received a rudimentary education in their families and parents taught them the

basics of religion. Early New England communities supported free public schools. Students from four to twenty years old studied in one-room schoolhouses where there was usually one schoolmaster for all grades. They learned reading, writing, and simple math. Boys usually went to school in the winter when there were fewer farm chores for them to do, while girls and younger children went to school in the summer. When their parents needed them to work at home, they did not go to school.

Feeling the need for a trained clergy, the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony made the decision in 1636 to establish a college. It was first named Cambridge, after the university where Puritanism had its birth. Later the name was changed to Harvard after a benefactor of the school.

As the colonies became more settled, upper-class boys might progress to private schools where they studied higher math, history, Greek, Latin, philosophy and science. Lower-class boys often did trade apprenticeships which lasted anywhere from 3-10 years. Opportunities for girls were more limited.

Hygiene

For all the lovely sights and sounds of the growing American Colonies, there were also the odors—a reality of life. People didn't bathe very often during this time, relying on the rubbing action of linen underclothing to fend off dirt and sweat. When it did come time to wash themselves - or their clothes - American colonists used soap made from animal fat and wood ashes. For dental hygiene, those fortunate enough to own toothbrushes might use bicarbonate of soda as toothpaste. For both the lower and upper classes, the lack of emphasis on cleanliness created a world where lice, fleas, and intestinal worms were regular concerns.

For all the lovely sights and sounds of the growing American Colonies, there were also the odors—a reality of life. People didn't bathe very often during this time, relying on the rubbing action of linen underclothing to fend off dirt and sweat. When it did come time to wash themselves - or their clothes - American colonists used soap made from animal fat and wood ashes. For dental hygiene, those fortunate enough to own toothbrushes might use bicarbonate of soda as toothpaste. For both the lower and upper classes, the lack of emphasis on cleanliness created a world where lice, fleas, and intestinal worms were regular concerns.

Infant hygiene was a similar story, as cloth diapers were often re-used and rarely changed. When they were removed, the infant's bottom was dry-wiped and generally powdered with wood dust, while the urine-soaked clothes were dried by the fire.

Medicine

Medicine of the 1700s was burdened by misguided ideas about the human body and a lack of generalized medicinal practices. Therapies such as bleeding, purging, and blistering were prescribed by doctors. A common medicine was Calomel, a form of mercury,

used as a laxative and disinfectant.

Not only did bad medical techniques kill many Americans, but diseases such as smallpox, malaria, tuberculosis, and pneumonia also took their toll. Infant mortality, diseases and lack of medical knowledge caused life expectancy to be an average of around 39 years old, although, of course, many people who survived childhood lived to be much older.

Medical innovations

Medical innovations

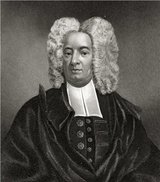

In New England, smallpox struck about every twelve years and killed a third of those infected, while leaving many survivors badly scarred and blind. In 1721, the minister Cotton Mather teamed up with Dr. Zabdiel Boylston to inoculate members of their own families and others to prove that the procedure saved lives. This involved taking pus from the blisters of someone who was infected and inserting it under the skin of a healthy person. The inoculated person usually developed a milder form of the illness, recovered, and was them immune. Mather had lost three children to smallpox and was desperate to save others from the same tragedy, as well as to preserve the lives of his other children. He first heard of the procedure from an African slave he had purchased, who told Mather his tribe practiced it.

Although Boylston and Mather had the support of the clergy, physicians and many of the common people of Massachusetts were horrified, until news spread that Bolyston's son and slave had both recovered from the disease. Mather published the results of the 1721 experiments and even convinced the royal family to inoculate.

Religion

For the Pilgrims and the Puritans, a church congregation and a town were synonymous. Even though many of the colonists had left Europe to escape religious persecution, the mix of different religions trying to find a foothold in the New World caused a whole new kind of tension. Churches often made extremely strict demands on those in their community, and any non-conformists could face some harsh penalties—from public whippings to imprisonment. The Rev. William Blackstone, Anne Hutchinson, Roger Williams, Rev. Thomas Hooker and his congregation, and the Weymouth followers of the Rev. Samuel Newman found it necessary to move south to establish their own communities.

For the Pilgrims and the Puritans, a church congregation and a town were synonymous. Even though many of the colonists had left Europe to escape religious persecution, the mix of different religions trying to find a foothold in the New World caused a whole new kind of tension. Churches often made extremely strict demands on those in their community, and any non-conformists could face some harsh penalties—from public whippings to imprisonment. The Rev. William Blackstone, Anne Hutchinson, Roger Williams, Rev. Thomas Hooker and his congregation, and the Weymouth followers of the Rev. Samuel Newman found it necessary to move south to establish their own communities.

Eventually more religions started to appear in the colonies and religious diversity became an unavoidable reality of life. Still, the majority of people went to their church regularly and practiced fervently.

First Great Awakening, 1732

The First Great Awakening, revitalized Christianity on a personal level by instilling a powerful sense of the need for salvation. Followers witnessed sermons by famous preachers such as Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield, which often led to questions about personal salvation.

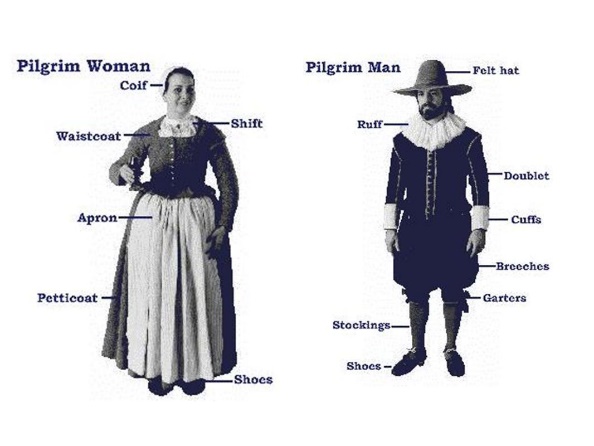

Clothing

https://www.plimoth.com/products/coif-adult

Pilgrim and Puritan clothing was colorful and reflected European clothing styles in the 1600s.

Pilgrim and Puritan clothing was colorful and reflected European clothing styles in the 1600s.

Until about the age of eight, children--both boys and girls wore gowns with a full- length skirt, high neckline, and long sleeves. The gowns were laced up and fastened in the back. Older boys and older girls wore smaller versions of adult clothing.

The undergarment for a woman was a calf-length, off-white, short-sleeved linen shift or smock, which somewhat resembled a nightshirt. In fact, shifts were worn for sleeping. For day, one or more ankle-length, skirts, called “petticoats,” were worn over the shift. Women also put on stays. The stays were stiffened with rows of stitching or reeds, to support and shape the body to fit the clothes. A bodice or waistcoat was worn over the top. It looked like a long-sleeved close-fitting jacket. Sleeves might be laced to the bodice. The waistcoat could be the same color as the skirt or a different color. Women's hair was always pulled tightly back and gathered under a coif.

Men wore a knee-length short-sleeved,

off-white linen shirt, which also served as underwear. On top of that they wore a doublet, which was relatively close-fitting, with long sleeves, broad padded shoulders, and buttoned down the front with tabs at the waist. Older or more revered men

often wore a full-length wool gown over the top of everything else.

Men wore a knee-length short-sleeved,

off-white linen shirt, which also served as underwear. On top of that they wore a doublet, which was relatively close-fitting, with long sleeves, broad padded shoulders, and buttoned down the front with tabs at the waist. Older or more revered men

often wore a full-length wool gown over the top of everything else.

Some clothes were worn by both men and women. Everyone wore stockings to cover their legs. The stockings came up over their knees and were tied with ribbons called garters to keep them up. Everyone wore leather latchet shoes or sturdy boots on their feet.

Everyone wore aprons to help keep their clothes clean. Women’s aprons were long and made of linen or wool. Men’s aprons were shorter and sometimes made of leather. Women wore their aprons all day; men usually wore aprons if they were practicing a trade like blacksmithing or carpentry.

All people wore something around their necks. Most people wore ruffled or flat collars of linen cloth. Some had lace on their collars. Some women wore a kerchief of linen around their necks. Both men and women sometimes added detachable cuffs to their bodices and doublets.

Everyone also wore something on their heads. Men and boys wore Monmouth caps knitted of wool, or wide brimmed hats made

of felt. Women too wore felt hats over their coifs. In cold weather, everyone wore cloaks or coats of

wool. They also wore mittens or gloves to keep their hands warm.

Everyone also wore something on their heads. Men and boys wore Monmouth caps knitted of wool, or wide brimmed hats made

of felt. Women too wore felt hats over their coifs. In cold weather, everyone wore cloaks or coats of

wool. They also wore mittens or gloves to keep their hands warm.

Fashions were constantly evolving. As time went on, men’s breeches became more fitted and jackets became longer. Women’s long flowing skirts were often paired with a blouse with a low neckline and a separate half-blouse with a modest high neckline. Bonnets, straw hats, mob caps, or other head covers were often worn outside by women. Wigs, however, were worn almost exclusively by men, and remained a staple of fashion through the American Revolution and into the early 19th century.

Diet

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuisine_of_the_Thirteen_Colonies

The seeds the Pilgrims brought with them did very poorly in the growing conditions of New England, so they came to rely on the crops Tisquantum taught them to grow and the seafood and game he taught them to catch. These continued to be the staple items in the colonists’ diet until after the Revolutionary War.

Seafood was plentiful year-round, and meat might come from deer, bear, bison, or turkey. Vegetables boiled together with meat were popular in New England. People also gathered roots and herbs along with native fruits such as blueberries and cranberries. Eventually, crops of onions, carrots and cabbage added variety to the settlers’ diet, and orchards contributed apples to the available fruit. New Englanders loved to bake. Apple pie and stuffed, baked turkey had their origins there.

Maize, beans and pumpkins were the “three sisters” grown together by the native peoples. The colonists were already familiar with pumpkins, which had been the “standing dish” – that is, the one served at every meal – in England. The colonists probably did not realize that pumpkins were native to the Americas and had been introduced to Europe just over a hundred years earlier by Christopher Columbus.

Baked beans and pease porridge were served with coarse, dark bread. Wheat was hard to come by, so bread was often made with rye and maize. Coarsely ground maize was also stirred into boiling water or milk to form a porridge called “Hasty

Pudding.” Sometimes this was only seasoned with salt, but it could also be sweetened, seasoned with cinnamon, fruit added and served with melted butter or cream – the original American comfort food. The salted corn porridge could be fried to form

a flat Johnny cake or journey cake. Revolutionary War soldiers carried rations of salt and corn meal in their packs that they could cook up when there was an opportunity. The British mockingly sang “Yankee Doodle” where the soldiers in camp were “thick

as hasty pudding.”

Baked beans and pease porridge were served with coarse, dark bread. Wheat was hard to come by, so bread was often made with rye and maize. Coarsely ground maize was also stirred into boiling water or milk to form a porridge called “Hasty

Pudding.” Sometimes this was only seasoned with salt, but it could also be sweetened, seasoned with cinnamon, fruit added and served with melted butter or cream – the original American comfort food. The salted corn porridge could be fried to form

a flat Johnny cake or journey cake. Revolutionary War soldiers carried rations of salt and corn meal in their packs that they could cook up when there was an opportunity. The British mockingly sang “Yankee Doodle” where the soldiers in camp were “thick

as hasty pudding.”

Military

www.varsitytutors.com › early-america-review › volume-5 › soldiers-

hartnation.com › the-colonial-militia-during-the-revolutionary-war

allthingsliberty.com › 2013/12 › militia-continentals

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minutemen

Laws in the British colonies required all able-bodied men between 16 and 60 to enroll in a militia, receive training, and serve in the military during periods of war. Individual towns had their own militias. Militiamen did not receive extensive training: sometimes as little as four days per year. Elite groups known as minutemen, were selected from the militiamen to receive additional training, and formed a highly mobile, rapidly deployed force which could respond to emergencies quickly.

Laws in the British colonies required all able-bodied men between 16 and 60 to enroll in a militia, receive training, and serve in the military during periods of war. Individual towns had their own militias. Militiamen did not receive extensive training: sometimes as little as four days per year. Elite groups known as minutemen, were selected from the militiamen to receive additional training, and formed a highly mobile, rapidly deployed force which could respond to emergencies quickly.

Full-time colonial soldiers known as "Rangers" patrolled the frontier to help ward off attacks by the French and Native Americans, since British soldiers were not accustomed to the American landscape. The Rangers often served as scouts or guides to locate targets for the militia or other troops.

The colonists resisted the idea of a standing army, because they felt it could be a threat to their own freedom. However, as things moved toward revolution, the Second Continental Congress established a Continental Army on June 14, 1775. George Washington was elected Commander-in-Chief. Local militia units were expected to provide backup for these “regulars.”

During the Revolutionary War, privates were paid the equivalent of $6.25 per month. Soldiers had to buy their own uniforms, gear, and weapons. Muskets were the preferred weapon for many soldiers, and while these long guns could do considerable damage, they could also take upwards of 20 to 30 seconds to reload.

Entertainment

https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/colonial-era-leisure-and-recreation

https://warontherocks.com/2015/04/the-colonial-tavern-crucible-of-the-american-revolution

https://colonistsdailylives.weebly.com/recreation.html

Initially, no one had much leisure time to enjoy, but recreation is a necessary tonic for days full of hard work. Music was the most common form of entertainment among the colonists, and The Bay Psalm Book (Boston, 1640) was the first book published in New England. Instruments such as the jaw harp, fiddle and flute were common.

Initially, no one had much leisure time to enjoy, but recreation is a necessary tonic for days full of hard work. Music was the most common form of entertainment among the colonists, and The Bay Psalm Book (Boston, 1640) was the first book published in New England. Instruments such as the jaw harp, fiddle and flute were common.

The Sabbath provided a day of contrast to the rest of the week. Church services of several hours were held in both the morning and the afternoon. Taverns, or “ordinaries,” were often built close to the church so that people who lived at a distance could take some refreshment between meetings. A separate parlor was sometimes provided for the women. In many New England towns, taverns were the only public meeting places besides the church. Men met there to hear the news, debate issues of the day, transact business, and play card games. Everyone drank alcoholic beverages, but drunkenness was punished.

Women were more likely to gather at quilting bees or sewing circles where they could talk and tell stories while they worked. High class women might invite friends to tea parties.

Social dancing was among the most popular forms of entertainment in the colonies. People danced three and four-handed reels and jigs at court days, weddings, fairs, house raisings, harvestings, and other festive gatherings, often to the music of a fiddle, flute or bagpipe.

There were also very early dancing schools in Boston which taught the Minuet, the cotillion, the quadrille and the allemande. Later dance instructors taught from The English Dancing Master by John Playford, first published in England in 1651. In 1684, Increase Mather gave an address condemning dancing, possibly because the dances were associated with Popish France and with the courts of England. Despite this, dancing schools continued to be in demand in the 18th century. English and Scottish country-dances became popular at public and private balls and assemblies, with accompaniment provided by a small orchestra. Plays were popular in England, and theater became prominent in America as well.

Puritan ministers preached against “blood sports” such as boxing, in which people were likely to be hurt, and sports which used a ball; but other forms of physical activities were accepted. Fairs or court days often began with horse racing, wrestling, jumping contests, and foot racing. People enjoyed swimming, boating, skating, fishing and hunting. Despite the prohibition on games involving balls, nine-pin bowling was accepted by the mid-1600s. The alleys beside taverns were often used for this game.

Both at home and at the tavern, people amused themselves with dice, card games such as whist and piquet, chess, checkers, dominoes, and cribbage. Wealthier families might have owned a backgammon game, and eventually, even a billiard table. An article on Colonial-Era Leisure and Recreation at Encyclopedia.com says, “Some critics condemned these games for their tendency to encourage gaming (gambling), and indeed, by the 1750s, gambling had become such an epidemic among the middle and upper classes in both England and America that many British plays, including Edward Moore's popular 1756 tragedy, The Gamester, addressed the addictive nature of the pastime. …”

“So prevalent were these activities throughout the colonies that when the Continental Congress met in 1774 to pass resolutions for the governance of the new nation, they expressly forbade the practice of gaming, cock fighting, horse racing, theatergoing, and all other diversions calculated to distract the minds of the colonists from the seriousness of the impending war with Great Britain.”

Housing

The original homes of the Plymouth Colony were crude, clapboard structures with dirt floors and thatched roofs. Later, among both the Pilgrims and the Puritans, houses tended to be simple, rectangular, and symmetrical, with side gables, similar to the houses they were familiar with in England. Garrison, Saltbox and Cape Cod styles were a response to the conditions in New England.

The original homes of the Plymouth Colony were crude, clapboard structures with dirt floors and thatched roofs. Later, among both the Pilgrims and the Puritans, houses tended to be simple, rectangular, and symmetrical, with side gables, similar to the houses they were familiar with in England. Garrison, Saltbox and Cape Cod styles were a response to the conditions in New England.

These were often one and a half or two-story wooden structures with shingled roofs. Each story had one to two rooms; some homes also included a loft or attic. Colonial homes had a central chimney or a chimney at each end, with fireplaces that were used both for heat and cooking.

Poorer colonists often had little furniture and stuffed their mattresses with straw. Houses were generally dimly lit, even in the daytime, and at night candles were used to provide light. During the 18th century more people began using whale-oil lamps for illumination.

Transportation

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/candc/factsheets/bostonpostroad.pdf

For most of the 17th and 18th centuries, roads were few and unreliable in Massachusetts, so water routes like the Connecticut River were important for moving both people and goods. In 1795 the South Hadley Canal opened on the river, followed by the Turner Falls Canal a few years later. These were some of the first canals in the country, making movement easier by allowing boats to bypass falls and other navigational hazards on the water. Massachusetts had several important harbors, including Boston and Salem, which allowed shipping of goods and people between coastal towns and across the Atlantic.

On land, people walked or rode horses. Men were assigned by town councils to lay out roads within their town, and to other nearby towns. These often followed existing Indian tracks as little as two feet wide, and portions were rocky and overgrown with bushes.

In 1673, a post route was laid out from New York to Boston. Post riders carried mail the 250-miles from city to city in two weeks. The Post Road became the most important thoroughfare of the colonies. By the end of the century, there were three different routes that made up the Post Road. As roads improved, wagons, carts and horse-drawn carriages were used for journeys. People without their own carriages sometimes traveled on a network of stagecoaches.

After the Revolutionary War, turnpikes and toll roads were chartered by the state and local governments but were managed and built by small corporations who charged a toll to use them.

Politics, Commerce and Currency

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saugus_Iron_Works_National_Historic_Site

https://www.computerimages.com/musings/massachusetts-shoe-industry.html

https://www.philadelphiafed.org/education/teachers/resources/money-in-colonial-times

https://newenglandtowns.org/new-england-hats

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massachusetts_Bay_Colony

Subsistence farming was common. Farmers mainly planted crops like corn or wheat for their families to eat, although some also produced tobacco or other cash crops to sell overseas and to other parts of the country. Widowed women often maintained a farm to help sustain their families.

Others made their living as tavern keepers, lumberjacks, carpenters, and blacksmiths. Younger, single women might find employment as maids or domestic servants. Commercial fishing and whaling was the lifeblood of many coastal communities, as was overseas trade.

Others made their living as tavern keepers, lumberjacks, carpenters, and blacksmiths. Younger, single women might find employment as maids or domestic servants. Commercial fishing and whaling was the lifeblood of many coastal communities, as was overseas trade.

The first integrated iron works in the Colonies was at Saugus, Massachusetts, northeast of Boston, where there was a supply of bog iron that could be mined. It was founded by John Winthrop Jr. and operated between 1646 and 1670, producing the iron used for nails, horseshoes, cookware, tools, and weapons by the Colonists and for products to export to England. The facility was powered by seven large waterwheels and there was a wharf to load the iron onto ocean-going vessels.

Shoemaking had been done in homes, or by itinerant craftsmen. In 1750, John Adam Dagyr came from Wales and settled in Lynn Massachusetts. He systemized shoe production by housing four to six craftsmen in small buildings called 10 footers. The shoes they made were marketed around the colonies by entrepreneurs. Many towns also had small hat factories which produced straw bonnets and palm-leaf hats.

An abundance of easily regulated waterpower was an important factor in the development of industry in New England and the Blackstone River Valley became home to the Industrial Revolution. Early textile factories produced yarn and woven fabric.

Colonial Coins

In the 1600s, currency took the form of pounds, shillings, and pence—the currency of the British Empire, which ruled the colonies until the Revolution, but it was extremely rare. Colonists used some forms of paper money but were forbidden from minting their own coinage . Therefore, many people traded or bartered for goods, food, and services. Wages and prices were often given in measures of Indian corn.

In time, some Spanish, Portuguese and French coins appeared in the colonies as a result of trade with the West Indies. The most famous of these was the Spanish Dollar, which served as the unofficial national currency of the colonies for much of the 17th and 18th centuries. With its distinctive design and consistent silver content, the Spanish dollar was the most trustworthy coin the colonists knew. To make change the dollar was actually cut into eight pieces, thus "pieces of eight" or “bits.”

Charles I was deposed in 1651 at the end of the English Civil War. In 1652, Massachusetts challenged England's ban on colonial coinage. The colony struck a series of silver coins, including the Pine Tree Shilling. All Pine Tree shillings were dated 1652, though they were produced for many years. If England found out about this illegal coinage, Massachusetts could claim it had not made any coins since 1652.

The government of England became fragmented after Cromwell’s death in 1658. In 1660, Charles II returned and was proclaimed king. By the early 1680s, relations between the government of Massachusetts and the administration of King Charles II had worsened considerably. Historian Louis Jordan says that “on October 23, 1684 Charles II abolished the charter of Massachusetts [Bay Colony], invalidating all of the laws of [Massachusetts] including the minting act of 1652,” In 1686, James II formed the Dominion of New England. Sir Edmund Andros was appointed governor by the crown, but he was resented by the colonists, who were used to selecting their own officials. When the colonists heard that James II had been deposed in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, they immediately arrested Andros and returned to the vacated charter, but people were worried that their government had no legal authority. When James daughter, Mary, and her husband, William III of Orange were invited to take the throne of England, Increase Mather acted as ambassador from the colonies to negotiate a new charter from the king and queen. The charter, written in 1691, combined the Massachusetts Bay Colony with the Plymouth Colony and some outlying areas, to form the Province of Massachusetts Bay. The King’s charter extended voting rights to non-Puritans.

Fire

Fire was a frequent event in colonial towns and cities. Where women in long skirts cooked in open fireplaces and homes and buildings were made partially or entirely out of wood, a house fire could start and spread from one structure to another. When a fire was spotted, the church bells rang and people cried a warning. Responding and assisting in putting the blaze out was the civic duty of any men in the vicinity. As early as the 1680s, Boston began building a fire department with the first paid firefighters in the colonies, even importing a hand-pumped fire engine from England.

On the 2nd of October 1711, a great fire raced through the center of Boston. It began at the Ship Tavern in the center of the city and consumed the Town House and the First Meeting House. It destroyed the homes of 110 families, and at least eight people were killed in the blaze, four of whom were sailors, crushed while trying to save the church bell of the First Meeting House.