Cambridge, Massachusetts

Also known as Newtowne

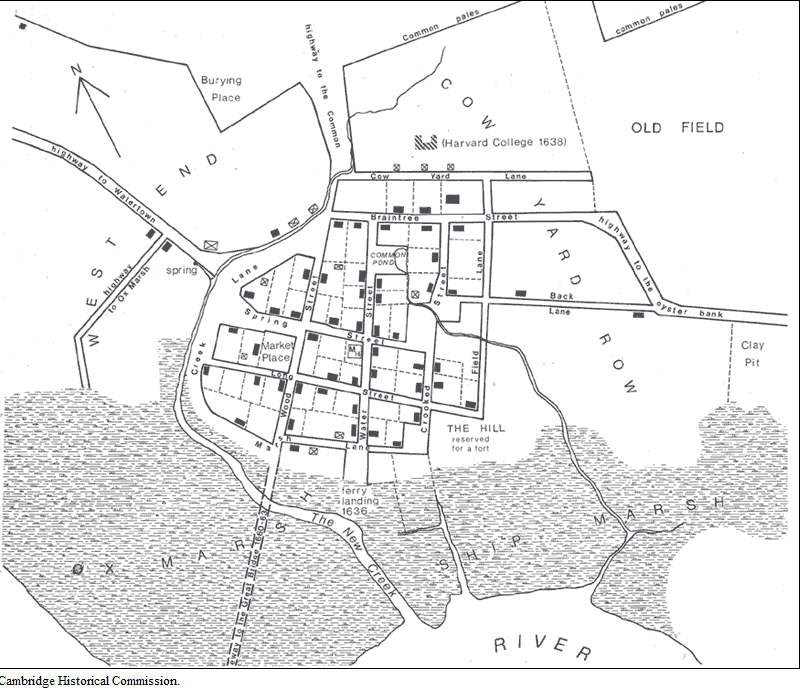

Six months after Gov. John Winthrop, and Deputy Gov. Thomas Dudley arrived in Boston in 1630, they, with others of their company sailed up the Charles River toward Watertown to look for a place to build a fortified capital for the Mass. Bay Colony. They were concerned that the Boston Peninsula was too susceptible to attack by ships of the French, Spanish, Dutch or other European powers competing for colonization rights. They chose a small hill rising from the tidal marshes on the north bank of the Charles River, at the entrance to a creek, 5 miles upstream from Boston. "It was far enough away from Boston Harbor to be protected. The banks were firm enough to provide a landing and the bottom could be dredged, an operation that was carried out in 1631-32. The Charles was deep enough at high tide to accommodate ocean-going ships, yet the winding channel and the limited maneuvering space at the landing would protect the town against pirate raids.

The History of Cambridge says,

"The town site was well graded for laying out an orderly system of streets, two springs promised adequate water, and the surrounding countryside was suitable for farming. In addition, the "highway" connecting Charlestown and Watertown--in reality, only a cross-country path--ran nearby. Opposite the new town, the south bank of the river was firm enough to allow the settlers to operate a ferry. The site, which they named Newtowne was officially selected on December 28, 1630 and Winthrop and Dudley, along with several other men agreed to build their homes there the next year. Streets and house lots were laid out in March, 1631.

"Newtowne seems to have differed from other communities founded by the Massachusetts Bay Company not only in its fortified character but in its well-ordered appearance, which probably reflected its early status as the capital. Whether the orderly grid of streets laid out for the "Towne" was the product of conscious planning, or simply a logical adjustment to a compact fortified site, the result was the earliest ordered urban plan in New England."

"Newtowne, was laid out with 64 house lots ranging from 1/8 to 3/4 of an acre, but even the smallest was large enough for a house and small barn. The area is bounded today by Eliot Square and Linden Street, Massachusetts Avenue and the River. A sense of compactness, order, and safety was ensured by the decree in January 1633 that "no houses be permitted beyond the pallisade" and that "by joint consent the town shall not be enlarged until all vacant places be filled with houses." Another order of 1633 required that "all houses within the bounds of the town shall be covered with slate or board, not with thatch." Each family owned a house lot in the village, planting fields outside, and a share in the common land.

"The impression of a tight little town is conveyed by William Wood in his New England's Prospect (1633): 'This is one of the neatest and best compacted towns in New England, having many fair structures with many handsome contrived streets.'"

The building began in 1631, with Dudley, Bradstreet and about eight other families completing homes; but John Winthrop changed his mind and moved his home to Boston, which caused a rift between him and Dudley. Gov. Winthrop wrote in his diary that the ministers had ordered the governor to procure a minister for New Town and contribute to his maintenance for an end of the difference between himself and the Deputy (Dudley.) Although Gov. Winthrop did not build his house there, Newtowne did serve as the capital of the colony.

At first, the only way from Newtowne to Boston was via the ferry from Charlestown to the north. Soon, a new ferry at the foot of Dunster Street began carrying passengers over the river to a path -- now North Harvard Street -- that led through Brookline and Roxbury, eventually traversing the spit of land that is now Washington Street. Until the Great Bridge was built in 1660-62, the ferries were the only way to Boston, eight long miles away and until the meeting house was built in Newtowne, the people there would have had to go to Boston to attend church.

In 1632, the Pallisade to fortify the town was built around the village at Dudley's expense. The surrounding communities were taxed to reimburse his expenditures. The earliest settlers had lots within the original impaled area and most of the house lots were identified in the records by their position in relationship to "the pales." Additional families began moving to Newtowne.

A company of about 20 families (members of the congregation of the famous and fiery Puritan preacher, Thomas Hooker), had come from Braintree, England in 1632. They started to settle at Mount Wollaston, but by order of the Court, they were required to move to New Town and arrived there in August. They approximately doubled the population of the town,

A meeting house was also built in 1632, but there was no minister until 1633 when the settlers of Newtowne sent an invitation to Thomas Hooker, who had been compelled to flee from England to Holland because of religious persecution. Mr. Hooker came, bringing with him the Reverend Thomas Stone as his assistant.

During the early decades Dunster Street was the principal high street. The first meetinghouse stood on the southwest corner of Mount Auburn Street, and at the foot of Dunster was the ferry landing, instituted in 1635. The street also contained the first tavern and thirteen of the town's fifty-seven houses. Another focal point was Winthrop Square. When Sir Richard Saltonstall returned to England in 1631, he forfeited the half-acre assigned him, and this was set aside as the marketplace. By 1635, Cambridge was one of four Massachusetts market towns, an honor in keeping with its importance as the capital.

West of Brattle Street creek and northwest from the College Yard were the two areas soon designated as West End and Pyne Swamp Field respectively. The first was that entire tract of upland lying north of the ox marsh and windmill marsh and bounded westerly by the Watertown line, i.e Sparks Street and Vassal Lane."

(Information from Norris: Cambridge Land Holdings, Cambridge Historical Society, April, 1933.) https://www.cambridgema.gov/historic/cambridgehistory.

The Rev. Hooker did not approve of the policy that only church members could become freemen. In addition, there was some rivalry between the Rev. Hooker and the Rev. John Cotton of Boston, and the Rev. Cotton being the more influential, Rev. Hooker determined to move his congregation to Connecticut, citing lack of space in Newtowne as a reason. The General Court offered them additional lands to the south of the Charles River if they would stay, but they chose to migrate, and about a hundred members of "Mr. Hooker's Company" began their march on May 31, 1636, eventually founding Hartford in the Colony of Connecticut. Only eleven families chose to remain in Newtowne.

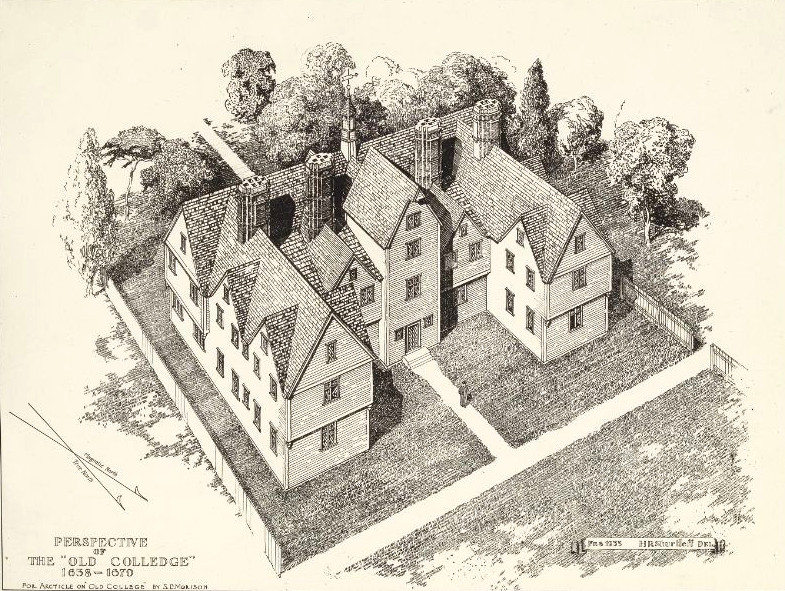

In 1636, the General Court made the decision to establish a college to train young men for the ministry and positions of leadership within the godly community. It was initially to be called Cambridge, after the college where the Puritan revolution had its birth, and the name of the town was changed to Cambridge in 1638 in anticipation. People subscribed to support the building of the college. The name of the college was later changed to Harvard, after Rev. Harvard, the minister of Charlestown, died and left his library and half his estate to the college.

By the time of the American Revolution, Cambridge was a quiet New England farming village clustered near the Common and the College. The majority of residents were descendants of the original Puritans -- farmers, artisans, and tradesmen, whose lives focused on Cambridge. Distinctly different were a small group of Anglicans -- barely a dozen households -- who lived apart from village affairs, relied on outside incomes, and entertained lavishly in grand homes along Tory Row (now Brattle Street). The Tories' houses and their church, Christ Church, still survive.

William Dawes rode out Massachusetts Avenue on his way to Concord on April 18, 1775. The following afternoon, four Cambridge Patriots died in a skirmish with retreating British regulars at the corner of Massachusetts and Rindge Avenues. The provisional government confiscated many Loyalist estates -- George Washington used the Vassal-Craigie-Longfellow House as his headquarters for nine months in 1775-6, and reviewed and trained the Continental Army on Cambridge Common. During the Siege of Boston, the General supervised the construction of three earthenwork forts along the Cambridge side of the Charles River. The remains of one, Fort Washington, can still be seen in Cambridgeport.

Johnson Direct Line Ancestors who lived in Cambridge

Places to visit in Cambridge

-

William and Mary Jared Mann's land grant at the corner of Sparks and Huron Street, running along Huron to Concord Ave.

-

Thomas Fisher's house lot was six lots west of the Mann's house lot, probably lying north of Huron Ave. (See the Cambridge map under "Thomas Mann."

-

The Concord Common. William Mann had a house lot on the common. This was also the site where George Washington reviewed and trained his troops when he took charge of the Continental Army.

-

The Old Burying Ground off from Harvard Square where William and Mary Mann are probably buried.

-

Cambridge First Parish Church -

-

Harvard Square and the old buildings of Harvard University where the Rev. Samuel Mann was a student.

-

Winthrop Square: site of the original marketplace in Newtowne/Cambridge. Mt Auburn St and John F. Kennedy St.

-

The Craigie/Longfellow House at the Longfellow National Historical Park on Brattle Street. $.

-

The Hooper-Lee-Nichols House on Brattle Street was built in 1685. It is the home of the Cambridge Historical Society and is open for tours on Tues. and Thurs. at 2, 3 and 4 PM for a cost of $5. Phone 617-547-4252.

-

Mt. Auburn Cemetery on Mt. Auburn St.