Plymouth, Massachusetts

Related articles: Duxbury, Plymouth Colony

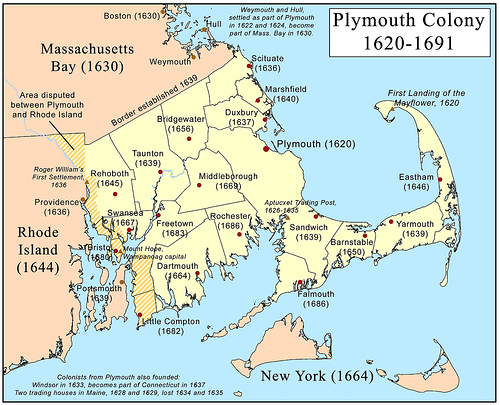

The Plymouth Colony was founded by religious separatists under the leadership of church elder William Brewster, Governor William Bradford and military leader Miles Standish. They had significant help from the Pokanoket/Wampanoag Sachem, Osamequin/Massasoit, and from Tisquantum, the last remaining member of the Pautuxet Tribe, on whose land they were building their Plantation.

Immigration and Population

One hundred and two passengers left England on the Mayflower. There was one death at sea, and one birth, Oceanus Hopkins. While anchored off Cape Cod, 4 passengers died, including Dorothy Bradford, the wife of William Bradford. One more baby, Peregrine White, was born. So when the Mayflower dropped anchor at Plymouth Harbor on Dec. 16, 1620, there were 99 “first-comers.” Over that winter, 44 more people died, and after the time the Mayflower departed for England, there were five more deaths, leaving 50 people in the colony.

With the help of Tisquantum, the people of Plymouth did manage to have a harvest in 1621, leading to the famous Harvest Celebration shared with the local Indians. However, supplies were still marginal when the ship Fortune arrived in Nov. 1621. Many of the 35 colonists onboard were family members of those who had come on the Mayflower; but Thomas Weston, the Plymouth backer, had sent none of the needed supplies. The colony now had 85 members, and this strained the available resources even further.

In 1622, three ships sent by Thomas Weston arrived in Plymouth, but they were bound for Wessagusett, to try to set up a colony there, and again, they had no provisions for Plymouth. The 67 men on the ships stayed through July and August before moving on.

“Remarkably, in 1623 Bradford told John Pory, a visitor to Plymouth, that "for the space of one whole year of the two wherein they had been there, died not one man, woman or child."

The Department of Historical Archeology at the University of Illinois says, “In July 1623, two more ships, the Anne under the command of Captain 'Master' William Peirce and Master John Bridges and the Little James under Captain Emanuel Altham, arrived carrying some 90 new settlers, including our ancestor, Stephen Tracy. This new group posed a different problem. Sixty of them were sponsored by the joint stock company, and therefore were obligated to work for the "common good" of the colony. But thirty others were under no such obligation, having paid their own expenses. They were referred to as "the particulars," having come "on their particular." The Anne reached New Plymouth in July 1623 and the Little James, a week or two later. In addition to this group, Phineas Pratt and possibly two or three others from Weston's abandoned settlement at Wessagusett/Weymouth joined the people of Plymouth, bringing the total number to some 180 by mid-1623.

Bradford commented that of the sixty settlers who came to join the general body of settlers as distinct from those who came on their own particular, some were "very useful persons and became good members to the body; and some were the wives and children of such as were here already. And some were so bad as they were fain to be at charge to send them home again the next year" (Bradford, p. 127).”

According to Gleason Archer, (With Axe and Musket at Plymouth. New York: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1936.) "those who remained were not willing to join the colony under the terms of the agreement with the Merchant Adventureres. They had embarked for America upon an understanding with the Adventurers that they might settle in a community of their own, or at least be free from the bonds by which the Plymouth colonists were enslaved. A letter addressed to the colonists and signed by thirteen of the merchants recited these facts and urged acceptance of the newcomers on the specified terms." The new arrivals were allotted land in the area of the Eel River known as Hobs Hole, which became Wellingsley, a mile south of Plymouth Rock.

In March 1624, a ship bearing a few additional settlers and the first cattle arrived. The Jacob under command of Capt. Pierce, sailed from Bristol, England to Plymouth, MA in 1625.

The Department of Historical Archeology at the University of Illinois says, “A 1627 division of cattle lists 156 colonists divided into twelve lots of thirteen colonists each. [64] Another ship also named the Mayflower arrived in August 1629 with 35 additional members of the Leiden congregation. Ships arrived throughout the period between 1629 and 1630 carrying new settlers; though the exact number is unknown, contemporary documents claimed that by January 1630 the colony had almost 300 people. In 1643 the colony had an estimated 600 males fit for military service, implying a total population of about 2,000.”

Governance

In Plymouth Colony, it seems that a simple profession of faith was all that was required for acceptance to the church congregation . This was a more liberal doctrine than some other New England congregations, such as those of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, where it was common to subject those seeking formal membership to strict and detailed cross-examinations. There was no central governing body for the churches. Each individual congregation was left to determine its own standards of membership, hire its own ministers, and conduct its own business.[89]

The colony offered nearly all adult males potential citizenship in the colony. Full citizens, or "freemen," were accorded full rights and privileges in areas such as voting and holding office. To be considered a freeman, adult males had to be sponsored by an existing freeman and accepted by the General Court. Later restrictions established a one-year waiting period between nominating and granting of freeman status and also placed religious restrictions on the colony's citizens, specifically preventing Quakers from becoming freemen. Freeman status was also restricted by age; while the official minimum age was 21, in practice most men were elevated to freeman status between the ages of 25 and 40, averaging somewhere in their early thirties.

The General Court was both the chief legislative and judicial body of the colony. It was elected by the freemen from among their own number and met regularly in Plymouth, the capital town of the colony. As part of its judicial duties, it would periodically call a "Grand Enquest", which was a grand jury of sorts, elected from the freemen, who would hear complaints and swear out indictments for credible accusations. The General Court, and later lesser town and county courts, would preside over trials of accused criminals and over civil matters, but the ultimate decisions were made by a jury of freemen.

Mortalty Rates

Maternal mortality rates were fairly high; one birth in thirty resulted in the death of the mother, resulting in one in five women dying in childbirth.[110] However, "the rate of infant mortality in Plymouth seems to have been relatively low. In the case of a few families for which there are unusually complete records, only about one in five children seems to have died before the age of twenty-one. Furthermore, births in the sample [of about 90 families] come for the most part with relatively few "gaps" which might indicate a baby who did not survive. All things considered, it appears that the rate of infant and child mortality in Plymouth was no more than 25 per cent."[111]

Johnson Direct Line Ancestors who lived in Plymouth and Duxbury:

- Stephen Tracy (1596-1654) and Tryphosa Lee (1597- )

- George Partridge (abt 1617-1695) and Sarah Tracy (1623-abt 1708)

- Mercy Partridge

Places to visit in Plymouth

- Plimoth Plantation

- Hobbs Hole – Nook Rd. from Sandwich St. to the baseball diamond. –Area of Stephen Tracy’s original 3-acre land grant.

- Pilgrim Hall Museum

- Leiden Street

- Pilgrim Memorial State Park

- Brewster Gardens

- The Plimoth Grist Mill

- Richard Sparrow House

- Old Fort Museum

- 1809 Heritage House Museum

- National Monument to the Forefathers

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plymouth_Colony

https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/united-states-and-canada/us-history/plymouth-colony

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pilgrims_(Plymouth_Colony)

http://www.pilgrimhallmuseum.org/pdf/The_Plymouth_Colony_Patent.pdf

http://www.histarch.illinois.edu/plymouth/townpop.html

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t0js9v01x;view=1up;seq=14

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duxbury,_Massachusetts

https://www.town.duxbury.ma.us/historical-commission/pages/town-history

A History of the Town of Duxbury, Massachusetts, with Genealogical Registers by Justin Winsor

duxburyhistory.org/local-history/

Research of LaMont Healy, published in the Duxbury Clipper.